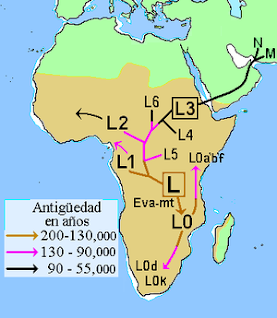

All living humans share a common point of origin in eastern Africa. Every person living today is descended from hunter-gatherers in Africa thousands of years ago. On our genetic profiles this appears as mtDNA

Macro-haplogroup L, also known as

Mitochondrial Eve/Eva. This should not be confused with the biblical Eve who lived no earlier than 7200 years ago.

Overview of the main divisions of haplogroup L.

About

300,000 years ago, people in Africa made

new kinds of stone tools and began transporting raw materials up to 250 miles (400 kilometers), likely through trade networks. By 140,000-120,000 years ago, people wore

animal skins and

pierced marine shell beads.

A

new genetic study indicates "The presence of eastern African ancestry as far south as Zambia, and southern African ancestry as far north as Kenya, indicates that people were moving long distances and having children with people located far away from where they were born. The only way this population structure could have emerged is if people were moving long distances over many millennia."

After a period of extensive population movements during which peoples from different regions intermarried, a change took place. Marriage partners were chosen from nearby.

The researchers used their study of Ancient DNA (aDNA) to create "the largest genetic dataset so far for studying the population history of ancient African foragers – people who hunted, gathered or fished. We used it to explore population structures that existed prior to the sweeping changes of the past few thousand years."

The DNA sampling was not uniform and not all of the individuals lived contemporaneously. However, "on average individuals from the same or nearby sites proved to be more closely related than predicted solely on the basis of the broad regional genetic structure, but this relatedness extends only over short distances, particularly within Malawi and Zambia."

This study focuses on population movements within Africa. It does not refer to the movements out of Africa. Stone tools dating to 1.5 million years have been found in Saudi Arabia near the Red Sea.

The oldest stone tool to be

found in Turkey reveals that humans passed through the gateway from Asia to Europe approximately 1.2 million years ago. The worked quartzite flake was found in ancient deposits of the river Gediz in western Turkey.

A trove of hand axes dating to 500,000 years ago was found in central Israel at

Jaljulya.

Thomas Strasser and Eleni Panagopoulou found stone tools on the southwestern shore of Crete, near Plakias. These date to between 200,000 and 100,000 years.

A young male was buried 100,000 years ago in

Qafzeh Cave in Lower Galilee.

Evidence of human habitation 100,000 years ago in the area of Bethlehem is attested along the north side of Wadi Khareitun where there are three caves: Iraq al-Ahmar, Umm Qal’a, and Umm Qatafa. These caves were homes in a wooded landscape overlooking a river. At Umm Qatafa archaeologists have found the earliest evidence of the domestic use of fire in Palestine.